|

By

far one of the most exciting developments in recent art is the

continuing confluence of Eastern and Western aesthetics. Finally those

once distant twains that, according to the racist Kipling, were never

supposed to meet, have not only met but merged with a vengeance, and we

are all the richer for it.

One

of the more auspicious examples to prove this point is the work of Mai

Cheng Zheng, a Chinese painter living and working in Oslo, Norway, whose

solo show "Feng-shui Art: Ancient Signs" can be seen from

November 28 through December 17 at Noho Gallery, 168 Mercer Street.

Although

the Chinese have been practicing feng-shui for four thousand years, most

Americans have only become familiar with the term in recent decades.

Feng-shui, which translates from Chinese as "wind and water,"

is the ancient science of arranging the elements of one's life,

particularly one's living and working spaces, to be in accord with

nature. Practitioners of feng-shui claim that the proper positioning of

one's desk or bed can have a profound affect on one's energy, one's

work, and other aspect's of one's life, bringing them into harmony with

nature and increasing not only one's creative efficiency but also one's

sense of well being.

Mai

Cheng Zheng took this longheld belief system a step further when she

began to apply the principles of feng-shui to the art of painting as a

student at Beijing's Central Academy of Arts and Design in the late 70s.

In 1981, however, after seeing an exhibition of works by the Norwegian

expressionist Edvard Munch in the National Gallery in Beijing, she

became enamored of Expressionism. Determined to study in Munch's

homeland, she was accepted at the State Academy of Arts in Oslo, and

later received a post graduate scholarship at the Art Academy in Bergen.

In

true multicultural fashion, the artist who became a Norwegian citizen in

1989, resumed her interest in feng-shui, teaching Norwegians to arrange

their working and living spaces more efficiently. At the same time, as a

-fine artist, she began reintroducing feng-shui principles, along with

more Western elements (such as her preference for oil paint over ink)

into her work as well.

Since,

Mai Cheng Zheng has become internationally known for her auspicious

synthesis of Eastern and Western aesthetics, with exhibitions in such

prestigious venues as the National Gallery in Beijing, where she first

discovered Munch, and Espace Bateau Lavoir in Paris, a gallery that once

represented Picasso. She has also exhibited in Germany, Belgium, and

Iceland, and had solo shows at Galleri Asur in Oslo.

In

her most recent exhibition at Noho Gallery, in Soho, the first thing

that strikes one about Mai Cheng Zheng's work is the balance that she

achieves between contemporary immediacy and timeless beauty. In

paintings at once funky and elegant, her use of fragmentary figurative

imagery and graffiti-like scrawls and signs within largely abstract

color areas can recall no less an enfant terrible of the untrammeled

gesture than the late JeanMichel Basquiat.

Mai

Cheng Zheng, however, employs such devices in a less aggressive and more

deliberate manner, to achieve balance and harmony rather than

dissonance. She accomplishes this by always balancing cold colors with

warmer ones. She also invariably sets up contrasts between forms and

shapes that are small and large, creating a sense of their being near or

far. Thus she brings the principles of yin and yang, or positive and

negative, which are the basis for feng-shui, to bear in her

compositions.

There

is an impulse toward the sumptuous and the exquisite that moors Mai

Cheng Zheng's work not in the monochromatic Literati tradition, from

whose gestural vivacity certain Abstract Expressionists drew

inspiration, but in much earlier 8th century Chinese tomb paintings,

with their combination of delicate linearity, earthy mineral colors, and

tactile fresco surfaces. Her use of vibrant reds, gold hues, and

glistening blacks, in combination with more subdued colors, harks back,

too, to the lacquered opulence of the Tang dynasty.

Then

there are disparate elements in Mai Cheng Zheng's personal semiotics

that refer even further back to prehistoric cave paintings: simplified

bisons, horses, antelopes, and other fanciful beasts, as well as rows of

running human figures laid down in slashing black strokes that in their

staggered urgency suggest the precise instant when images verged on

ideograms, that magical moment of metamorphosis when pictures became

written language. These signs are derived from sources as diverse as her

own Chinese heritage, Nordic runes, and Egyptian hieroglyphics, all of

which she combines to express universal commonalities.

Mai

Cheng Zheng also combines such archetypal signs with more contemporary

elements adopted from expressionism and action painting, such as skeins

and drips ala Pollock, to achieve dynamic juxtapositions of figure,

form, and gesture. Whiplash calligraphic strokes are employed quite

masterfully to animate the surfaces of her paintings in much that same

manner as Cy Twombly's scrawled phrases.

These

calligraphic elements are especially plentiful and energetic in Mai

Cheng Zheng's painting "Silk Road,"

where various staid rectangular forms are juxtaposed with a sinuous and

intricate network of linear shapes that dance in swarming profusion over

a surface further enhanced by partial scrapings revealing the layered

imagery that may be referred to as "aesthetic

archaeology." Here, the interaction between static and fluid

elements is especially dynamic, demonstrating this artist's belief that

"only when two opposite forces are acting together, do we get

energy."

By

contrast, "Inventor of the Wheel"

is a bold composition that juxtaposes superimposed rectangles in

brilliant red and yellow hues with the silhouetted figure of a man, a

wheel, and a rearing animal. In this painting, Mai Cheng Zheng's use of

texture is especially sensual, with striated impastos contributing

considerable tactile appeal to the overall design. An intriguing array

of smaller signs and symbols are scrawled within the rectangle

containing the central figures, and the painting is further enlivened by

four irregularly shaped roundish red forms that float down the right

side of the composition, providing a buoyant contrast to the more

austere geometric shapes.

A

fanciful array of symbols, depicting the graceful flight of various

creatures is the central focus of the painting entitled "The

Riders' Tale." Here, too, the overall composition is

apportioned into rectangular divisions, with two large squares

delineated in brilliant red, gold, and rainbow hues, dominating the

center, and two vertical rows of smaller gold squares bordering both

sides. This is an especially engaging painting, its compartmentalized

composition of interlocking "frames" suggesting an almost

cinematic sequencing, its lively pictographic imagery conveying the

sense of an epic narrative or myth.

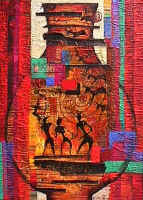

In

other paintings such as "The Movement

of History" and "The Jar of

Signs," Mai Cheng Zheng elaborates upon similar themes in

distinctly different ways. The latter painting is an interesting

compositional departure, with the boldly outlined contours of a large

vase surrounding various silhouetted human and animal shapes, suggesting

culture as a container for history, a receptacle for our common human

heritage.

Indeed,

it is precisely her ability to encapsulate archetypes and universal

themes in vital visual terms that makes the art of Mai Cheng Zheng

ultimately valuable and rewarding.

Byron

Coleman | ||||||